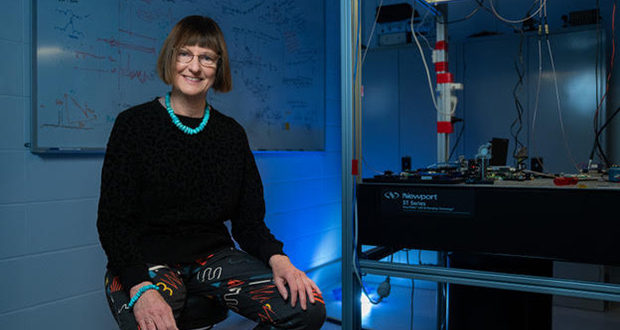

Distinguished Professor Susan Scott has always been interested in mathematics, but it was after watching the moon landing while in primary school that she developed her love for physics and gravity, a passion that still hasn't left her 53 years later.

“I was the only kid sitting there for hours. I was so inspired by seeing the images of the people leaping off the surface of the moon.

“This is definitely what really sparked my interest in gravity, which is my big thing,” Scott told Campus Review.

At that time living in suburban Melbourne, Scott was expected to become a hairdresser, a teacher or a nurse; but she has now been elected as a Fellow of the International Society on General Relativity and Gravitation (ISGRG), one of the highest distinctions in theoretical physics.

She is the first Australian to join the elite club which includes world renowned scientists like theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking and Nobel Laureates Roger Penrose and Kip Thorne.

“It's a very difficult thing to become part of, and [the nomination] was a very exciting and pleasant surprise.

“I had limited horizons, and if somebody had said to me what my career would look like, I would never have believed that.

“It's absolutely quite amazing to me, thinking back that it's actually all unfolded like this.”

Back in the day, there weren't a great range of expectations of what you could do in your life, Scott said, believing that without the all-girl school scholarship she received, she could have not had the opportunity to nurture her interests in science.

“We were led to believe that we could go on and do anything that we really tried hard enough and put our mind to.”

After finishing high school, Scott studied at Monash University for a Bachelor of Science in Pure Mathematics that she achieved with honours.

She then moved to the UK after winning a Rhodes Fellowship to expand her knowledge at the University of Oxford.

There, she spent four years with the relativity gravity group working with Professor Sir Roger Penrose, a famous mathematical physicist and Nobel Laureate.

“That was an amazing formative period.

“I think this experience really established all my international networks, which I still have today,” Scott added.

2015: an achievement 25 years in the making

After a couple of years in the UK, Scott returned to Australia where she settled in Canberra and started as a level A Postdoctoral fellow at the ANU.

It was in these early years that she started studying the singularities of spacetime, an area in which physics goes “really badly wrong”, where the curvature of spacetime becomes infinite and creates a black hole.

“I was researching how these form in the universe, which is really fundamental because as it turns out, the universe is full of black holes.”

In 1995, she joined the experimental side of wave detection where she started working with a group to develop the components of LIGO detectors, which would later be used to detect gravitational waves.

“At that time, there was no Australian effort on the science side of the gravitational wave project. I actually started that.

“We were also developing techniques for processing and analysing the immense amount of data that these detectors would take in."

It was in September 2015, 25 years after having started her research that Scott and the team achieved detection for the first time; a breakthrough discovery.

It was late at night that Scott received an email from her colleagues announcing that they had “a very interesting signal in the LIGO detectors in the last hour".

“It became clear pretty quickly that night that it was kind of the real thing, it seemed evident that we had a detection signal.

“And of course, you can't tell anyone outside of collaboration, by that time they were all in bed asleep, meaning I couldn't tell anyone at all.

“I had this incredible information, this was the science story of the century, and I absolutely couldn't tell anyone which meant really I couldn't sleep all night.

“I was like a kid at Christmas, it was so exciting," Scott says.

The team's discovery of gravitational waves opened a new ‘physics’ world to researchers as these waves do not fall under the electromagnetic spectrum but under a new and unexplored spectrum.

“Gravitational waves are an entirely new way of looking at the universe.

“We cannot observe them using our standard age-old techniques like light and radio. What we detected was two black holes circling around each other and actually smashing together and producing these strong gravitational waves from that collision.”

The discovery scientifically proved Albert Einstein's hundred-year-old theory that gravitational waves would be caused by a collision of massive objects in space such as black holes.

Scott said the project didn’t come without difficulties as for 25 years they had to wait for the moment to come; always having to convince other scientists and funding agencies to believe in them.

“Other scientists in other fields were very sceptical and there was a lot of disbelief that it was going to happen, and that that the waves were even real.

“It was hard to convince funding agencies to support our work when we didn’t have anything to show for 20 years: it was predicted science, but not tangible science that had come from the detections.

“We had no idea when it would happen, it was really a question of time, getting the instruments and technology sensitive enough to be able to detect these very small waves.

“It might sound strange, but we were never idle during all those years. We were full of activity and really ramping up our efforts towards what we believed would eventually be detection.”

Since then about 90 new detections have been made and all are bringing new information about the universe and its systems; information that researchers did not have before.

According to Scott, people believed that achieving detection would be the end, but it was just the tip of the iceberg.

“This was only the start, myself and my research group here, we want to detect gravitational waves coming from a neutron star which are a dense type of star in the universe.

“They're not very big, about the size of Canberra, but they're made of this incredibly dense material and we don't really understand much about them yet.

“And by eventually making detections of waves coming from those spinning neutron stars, we will be able to unlock a lot of secrets and information about neutron stars and their composition.”

In addition to working on neutron stars, Scott has also been appointed editor-in-chief of the prestigious international journal Classical and Quantum Gravity. She is the first Australian to be appointed to this position.

First Australian of many, but mostly first women scientist

While Scott's career has been astonishing with its many prizes and awards, she often found herself being the first Australian to achieve these, and she was also the first woman.

“I think it's been really quite tough coming from a period and a time when there were basically no women at all.

“I have encountered a lot of barriers and difficulties that I've had to overcome, it's been quite a difficult journey.”

Back in the days when Scott started as an undergraduate, she didn’t have any female lecturers during her studies: a “sobering” experience.

“I sort of wondered what the future held? Whether I could really actually forge a career in this field being a woman.”

In 2009, she and a colleague became the first female professors of physics at ANU.

“That did take them a long time, and obviously, you're going against the grain and that's a sort of barrier, a glass ceiling, if you like.”

Back in 2020, she was awarded the Prime Minister’s Prize for Science for her contribution to gravitational waves; she was the first woman physicist to gain this recognition.

“Again, it's kind of breaking through that sort of realm of past male recipients.

It's like a mental barrier, she said, both for the person being nominated but also for everyone else, because it hasn't happened previously.

“I talk to young women scientists a lot in my work one way or another and it is inspiring for them to see that things can be achieved. And I think that makes a big difference,” she said.

Fortunately, things are slowly but surely evolving for women in the field of science. Scott believes that the last 10 years have seen a real tangible change, but it is not enough yet.

In order to help further women's interest in STEM, including her own science area in gravity, she has joined a project called Einstein-First, which rolls out educational programs in schools from year three up to year 10, to introduce modern physics concepts in an interactive and engaging way to kids at an early age.

"I think it’s very important for Australia to continue to develop future talents, and personally, I feel that starting really early is the way to go."

In addition to sparking a scientific curiosity in the younger generation, Scott also wants to further Australia’s international position in the field which she believes is our future.

“Science is going to save the planet, we need to be thinking very carefully about what systems we need to put in place for sustainability, for climate change and how we can live our lives without being a burden."

Scott believes that to achieve sustainability, science needs to be taken into account to help inform public decisions and policy as scientists can bring an expert eye to the situation.

“Not to the exclusion of everything else, but that needs to always be thought of: science can make a real difference.”

Do you have an idea for a story?Email [email protected]

Campus Review The latest in higher education news

Campus Review The latest in higher education news