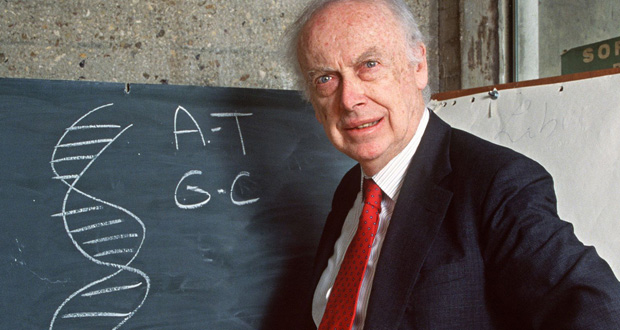

In 2007 James Watson, the Nobel Prize winner who co-discovered the structure of DNA, said that black people are genetically inferior. In an interview with the Sunday Times Magazine, he voiced that he was "inherently gloomy about the prospect of Africa" as "all our social policies are based on the fact that their intelligence is the same as ours, whereas all the testing says, not really".

Please login below to view content or subscribe now.

Campus Review The latest in higher education news

Campus Review The latest in higher education news